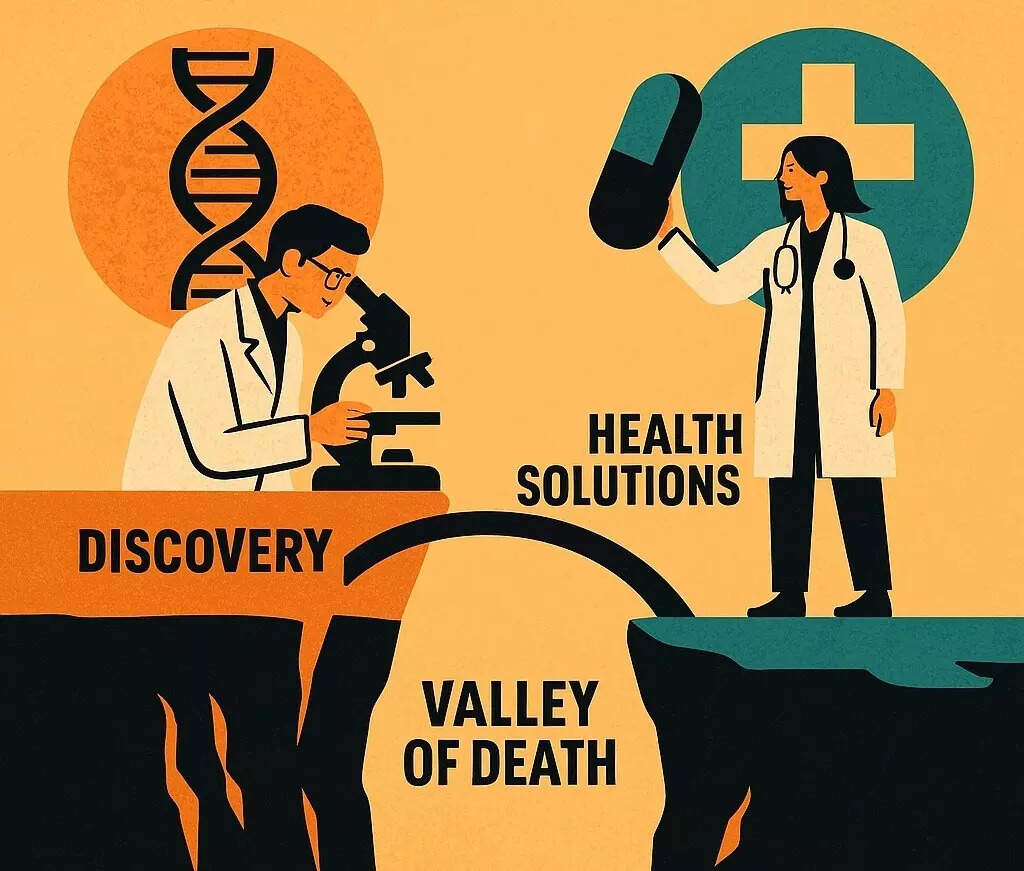

New Delhi: India has no shortage of scientific talent or discoveries in biosciences. But turning these breakthroughs into solutions that transform lives remains a systemic challenge. Bridging this gap—often called the “valley of death”—requires more than scientific brilliance. It demands structural reform, aligned incentives, and bold experimentation.

“This is the infamous ‘valley of death’ in translational research,” says Dr. Anurag Agrawal, Dean of the Trivedi School of Biosciences at Ashoka University. “It’s not always a technical issue. Often, people aren’t incentivised to go beyond publishing papers.”

To truly cross this chasm, he argues, India must reward translational impact alongside academic publishing. “We need to evolve institutions so that real-world outcomes matter in career progression,” Dr. Agrawal insists. “If stepping into translation brings only red tape and no reward, no one will do it.”

Systemic Fixes: Incentives, Incubators, and Innovation Missions

Among his recommendations are streamlining bureaucratic processes, scaling up initiatives like the Atal Innovation Mission, and building strong incubators that support not just ideation but implementation.

“These programs are a step in the right direction,” he says, “but they must be scaled thoughtfully to support productization and field deployment.”

Academia Meets Industry: Building a Bioscience Pipeline

On bridging academia and industry, Dr. Agrawal believes the solution lies in starting young. “We must ignite passion for innovation early—before students become exam-focused and risk-averse.”

At Ashoka, that vision is taking shape. The university is building an innovation centre physically integrated with the Trivedi School of Biosciences. Undergraduates are encouraged to engage with cutting-edge technologies from day one. “Biology today is interdisciplinary. AI is the new language of biology,” he declares.

Ashoka has also launched the Lodha Young Genius program, bringing high-school students—some as young as Class 9—face-to-face with leading thinkers like Nobel Laureate Paul Nurse. “These early sparks can light lifelong fires,” Dr. Agrawal says.

From Rare Disease Breakthroughs to Mainstream Health Innovation

India’s foray into genomics gained traction through the diagnosis of pediatric rare diseases using next-generation sequencing (NGS). But Dr. Agrawal sees the future in expanding these capabilities to more prevalent challenges like non-communicable diseases (NCDs), especially cancer.

“In oncology, genomic profiling helps personalise therapies using biomarkers like EGFR or ALK mutations,” he explains. However, such innovations remain largely confined to elite institutions due to cost barriers.

That’s changing. Companies like Karkinos healthcare and Strand Life Sciences, now backed by Reliance, are striving to democratise genomic diagnostics. “If Reliance can do for genomics what it did for telecom with Jio, we may finally see precision oncology become mainstream,” he notes.

Genomic Surveillance: A Public Good, Not a Private Gamble

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the critical role of genomic surveillance, but it also exposed gaps. “If a novel pathogen emerges in a district hospital, are we positioned to catch it early? Not yet,” says Dr. Agrawal.

Platforms like IDSP, IHIP, and INSACOG are steps forward, but genomic surveillance remains overly centralized and research-focused. To be effective, it must be embedded in public health systems, with strong federal coordination.

“Surveillance is a public good,” he stresses. “It cannot be left to the private sector. The government must lead—especially in a country where health is a state subject but surveillance is centrally governed.”

Precision Medicine—Broadening the Lens

Dr Agrawal urges a more inclusive understanding of precision medicine. “Even a continuous glucose monitor guiding a diabetic’s diet is precision health,” he says. In this broader view, AI, mobile tech, and wearable devices can bring personalised care to the masses.

However, a recurring bottleneck remains: access to targeted therapies. “Genomic diagnostics mean little without affordable access to the corresponding drugs,” he warns. India must align diagnostics with treatment availability, regulatory flexibility, and pricing reforms.

Commenting on what should the National Research Foundation prioritise?, Dr Agarwal informed that the NRF could play a transformative role—if it focuses on people, not just infrastructure. “Fund curiosity. Fund mentorship. Don’t micromanage outcomes,” Dr. Agrawal advises. “If we invest in passionate researchers and capable institutions, the impact will follow.”

The Road Ahead: From Talent to Translation

India’s aspirations in genomics and health innovation are not limited by scientific capability—they’re constrained by outdated systems. To unlock the full potential of Indian biosciences, Dr. Agrawal calls for a culture that rewards real-world outcomes, fosters interdisciplinary education, and supports translation at every step.

“Ashoka University may be small, but we can be a lab for the country—where we test bold ideas that scale,” he says. “India has the talent and the tech. Now, we need to align incentives and invest in the right structures. Only then can we truly democratise health innovation.”