ATLANTA — President Donald Trump’s executive order seeking to overhaul how U.S. elections are run includes a somewhat obscure reference to the way votes are counted. Voting equipment, it says, should not use ballots that include “a barcode or quick-response code.”

Those few technical words could have a big impact.

Voting machines that give all voters a ballot with one of those codes are used in hundreds of counties across 19 states. Three of them — Georgia, South Carolina and Delaware — use the machines statewide.

Some computer scientists, Democrats and left-leaning election activists have raised concerns about their use, but those pushing conspiracy theories about the 2020 presidential election have been the loudest, claiming without evidence that manipulation has already occurred. Trump, in justifying the move, said in the order that his intention was “to protect election integrity.”

Even some election officials who have vouched for the accuracy of systems that use coded ballots have said it’s time to move on because too many voters don’t trust them.

Colorado’s secretary of state, Democrat Jena Griswold, decided in 2019 to stop using ballots with QR codes, saying at the time that voters “should have the utmost confidence that their vote will count.” Amanda Gonzalez, the elections clerk in Colorado’s Jefferson County, doesn’t support Trump’s order but believes Colorado’s decision was a worthwhile step.

“We can just eliminate confusion,” Gonzalez said. “At the end of the day, that’s what I want — elections that are free, fair, transparent.”

Whether voting by mail or in person, millions of voters across the country mark their selections by using a pen to fill in ovals on paper ballots. Those ballots are then fed through a tabulating machine to tally the votes and can be retrieved later if a recount is needed.

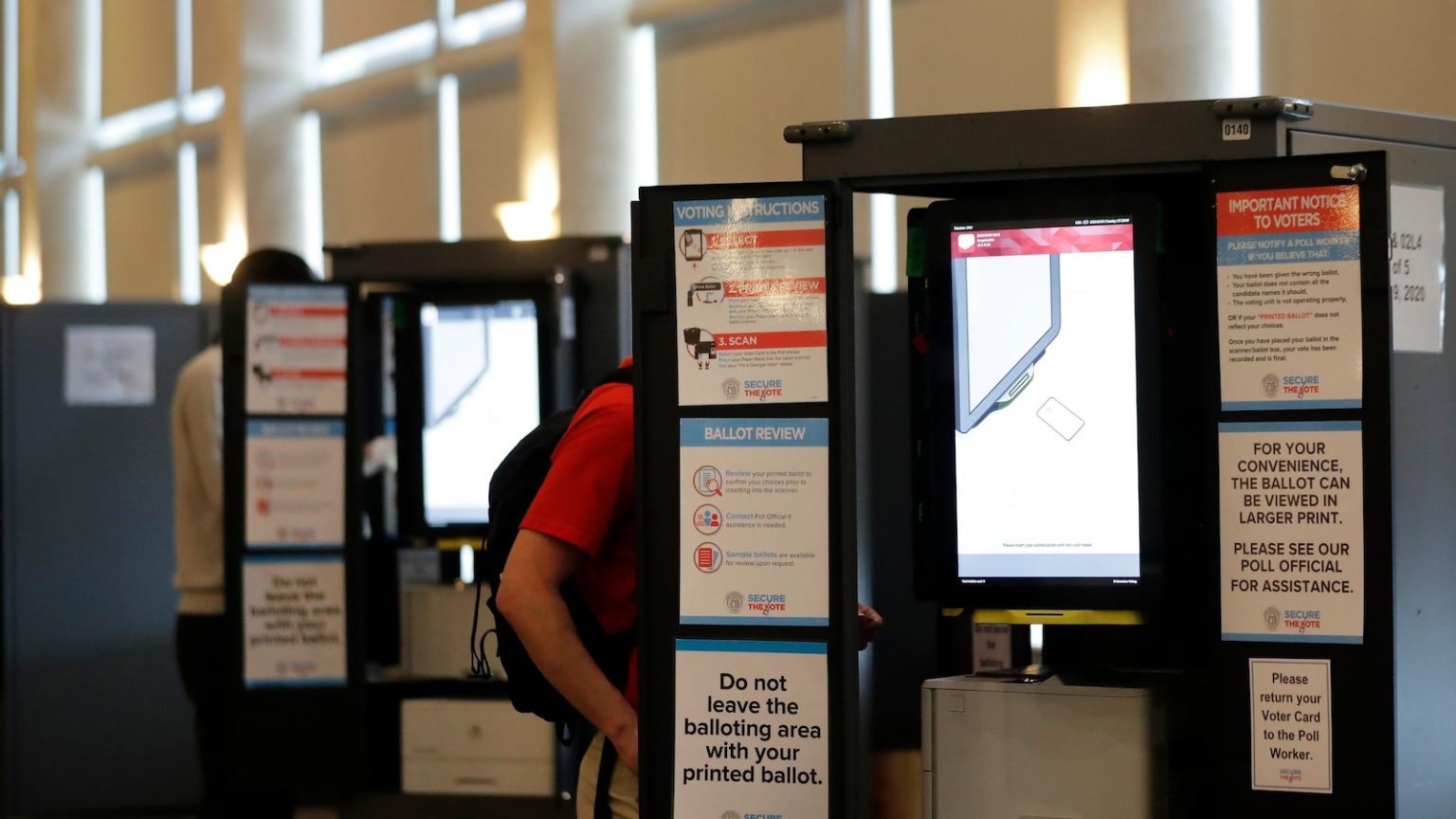

In other places, people voting in person use a touch-screen machine to mark their choices and then get a paper record of their votes that includes a barcode or QR code. A tabulator scans the code to tally the vote.

Election officials who use that equipment say it’s secure and that they routinely perform tests to ensure the results match the votes on the paper records, which they retain. The coded ballots have nevertheless become a target of election conspiracy theories.

“I think the problem is super exaggerated,” said Lawrence Norden of the Brennan Center for Justice. “I understand why it can appeal to certain parts of the public who don’t understand the way this works, but I think it’s being used to try to question certain election results in the past.”

Those pushing conspiracy theories related to the 2020 election have latched onto a long-running legal battle over Georgia’s voting system. In that case, a University of Michigan computer scientist testified that an attacker could tamper with the QR codes to change voter selections and install malware on the machines.

The testimony from J. Alex Halderman has been used to amplify Trump’s false claims that the 2020 election was stolen, even though there is no evidence that any of the weaknesses he found were exploited.

Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, a Republican, has defended the state’s voting system as secure. In March, the judge who presided over Halderman’s testimony declined to block the use of Georgia’s voting equipment but said the case had “identified substantial concerns about the administration, maintenance and security of Georgia’s electronic in-person voting system.”

Trump’s election executive order is being challenged in multiple lawsuits. One has resulted in a preliminary injunction against a provision that sought to require proof of citizenship when people register to vote.

The section banning ballots that use QR or barcodes relies on a Trump directive to a federal agency, the U.S. Election Assistance Commission, which sets voluntary guidelines for voting systems. Not all states follow them.

Some of the lawsuits say Trump doesn’t have the authority to direct the commission because it was established by Congress as an independent agency.

While the courts sort that out, the commission’s guidelines say ballots using barcodes or QR codes should include a printed list of the voters’ selections so they can be checked.

Trump’s order exempts voting equipment used by voters with disabilities, but it promises no federal money to help states and counties shift away from systems using QR or barcodes.

“In the long run, it would be nice if vendors moved away from encoding, but there’s already evidence of them doing that,” said Pamela Smith, president of the group Verified Voting.

Kim Dennison, election coordinator of Benton County, Arkansas, estimated that updating the county’s voting system would cost around $400,000 and take up to a year.

Dennison said she has used equipment that relies on coded ballots since she started her job 15 years ago and has never found an inaccurate result during postelection testing.

“I fully and completely trust the equipment is doing exactly what it’s supposed to be doing and not falsifying reports,” she said. “You cannot change a vote once it’s been cast.”

In Pennsylvania’s Luzerne County, voting machines that produce a QR code will be used in this year’s primary. But officials expect a manufacturer’s update later this year to remove the code before the November elections.

County Manager Romilda Crocamo said officials had not received any complaints from voters about QR codes but decided to make the change when Dominion Voting Systems offered the update.

The nation’s most populous county, Los Angeles, uses a system with a QR code that it developed over a decade and deployed in 2020 after passing a state testing and certification program.

The county’s chief election official, Dean Logan, said the system exceeded federal guidelines at the time and meets many of the standards outlined in the most recent ones approved in 2021. He said postelection audits have consistently confirmed its accuracy.

Modifying or replacing it would be costly and take years, he said. The county’s current voting equipment is valued at $140 million.

Perhaps nowhere has the issue been more contentious than Georgia, a presidential battleground. It uses the same QR code voting system across the state.

Marilyn Marks, executive director of the Coalition for Good Governance, a lead plaintiff in the litigation over the system, said her group has not taken a position on Trump’s executive order but said the federal Election Assistance Commission should stop certifying machines that use barcodes.

The secretary of state said the voting system follows Georgia law, which requires federal certification at the time the system is bought. Nevertheless, the Republican-controlled legislature has voted to ban the use of QR codes but did not allocate any money to make the change — a cost estimated at $66 million.

Republicans said they want to replace the system when the current contract expires in 2028, but their law is still scheduled to take effect next year. GOP state Rep. Victor Anderson said there is no realistic way to “prevent the train wreck that’s coming.”

___

Associated Press writer Christina A. Cassidy contributed to this report.

___

Kramon is a corps member for The Associated Press/Report for America Statehouse News Initiative. Report for America is a nonprofit national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on undercovered issues. Follow Kramon on X: @charlottekramon.