New Delhi: A study analysing brain scans of crew members who spent a year at an Antarctic research station has revealed changes due to exposure to isolated and extreme environments with potential impacts on physiology and cognition.

The findings, published in the journal ‘npj Microgravity’, have implications as extended space missions are planned from around the world, researchers said.

The team from the US, Europe, Australia and New Zealand found an overall reduction in white matter and a reduced grey matter in brain regions known to help with memory, language and spatial awareness.

Astronauts experience considerable stress in space, and understanding its effects on the brain can aid in assessing risks and building resilience, the researchers explained.

They pointed out that analogue environments – locations on Earth with features similar to those found on the Moon or Mars- such as the Antarctic Concordia Station, simulate “isolated, confined, and extreme” (ICE) conditions.

The findings are also relevant for individuals in the general population where a perception of isolation — or loneliness — has been on the increase, and many have experienced chronic stress over the past years, the team said.

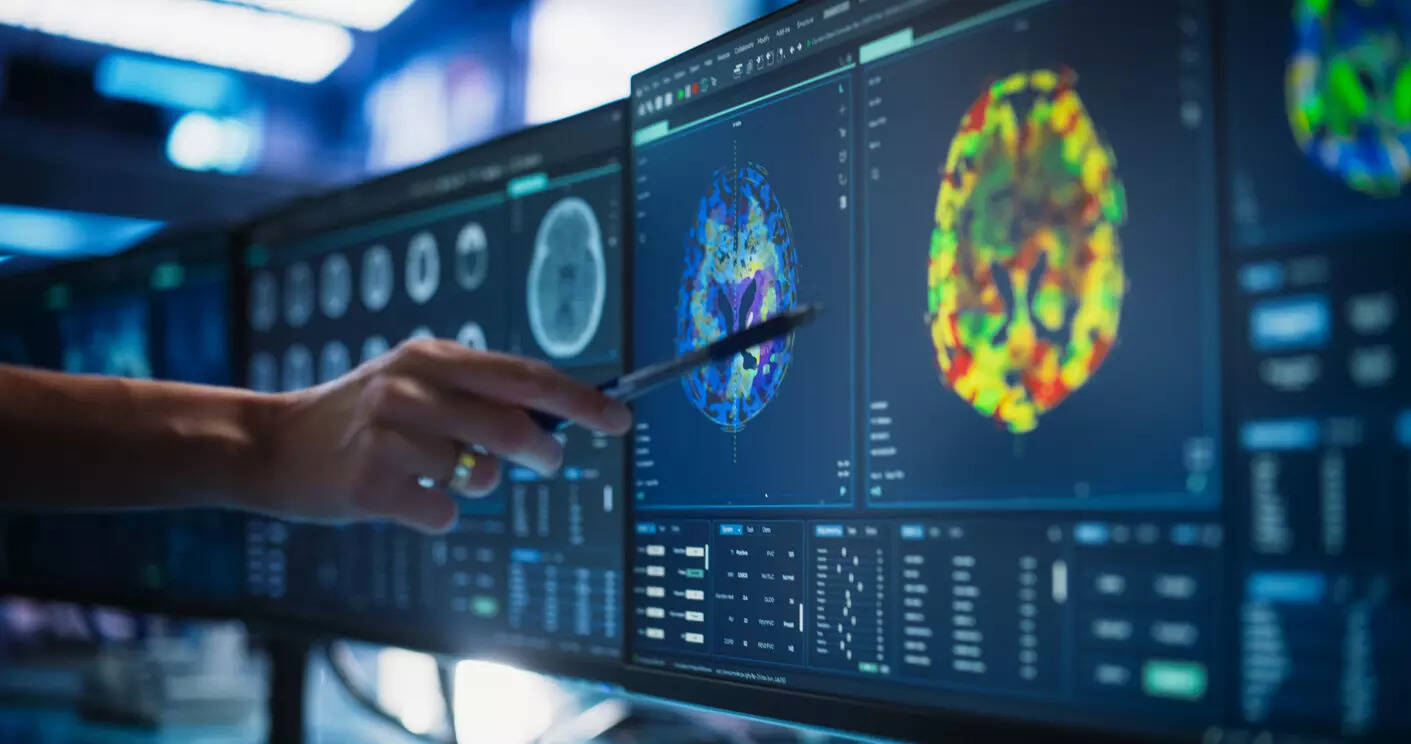

The researchers, including those from the University of Pennsylvania and the New Zealand Brain Research Institute, analysed MRI scans of 25 crew members who spent 12 months at Concordia (a French-Italian research facility).

The scans, taken before the mission, immediately after, and five months post-mission, were compared with those of another 25 individuals not subjected to isolated, extreme conditions.

The team found an overall reduction in white matter, along with decreased grey matter in the brain’s temporal and parietal lobes, hippocampus, and thalamus. These regions are critical for processing sensory information, memory, language, and spatial awareness.

While it is known that white and grey matter naturally decrease with age- leading to age-related cognitive decline- other factors like diseases and lifestyle choices can also contribute to these reductions.

The study revealed that improved sleep and physical activity, such as gymming, during periods of isolation and confinement were linked to a lesser loss of grey matter, suggesting that lifestyle choices may have protective effects.

Moreover, the levels of white and grey matter were observed to return to pre-exposure levels five months after the participants returned from Antarctica.

“Life in space and on Earth entails exposure to and requires resilience to stress. Elucidating the effects of prolonged stress in extreme conditions highlights significant, but transient brain changes relevant for optimal physiological and cognitive functioning,” the authors wrote.

“The current data and future studies in (isolated, confined and extreme) environments, including space travel, reemphasise the need to identify specific countermeasures that may mitigate changes in brain anatomy when individuals are isolated,” the team wrote.

“The relevance of the current findings has broadened with the increase in isolation in the general population,” they further noted.